Sensations, not words

Baines, L. A. (2012). Sensations, not words. Journal of the Washington Academy of the Sciences 98(3), 1-18.

The written word has served as an important mode of communication for thousands of years. The twenty-first century promises to deliver increasingly sophisticated, always-on machines that use sensory stimuli, such as images and sound, not words, as basic units of communication. The shift from words to sensations has implications for how we think, what we think, and how we feel about what we think. This paper describes the current state of the transition from words to sensations, and explores some potential gains and losses.

As people write and read less, while watching television and using telephones, computers, and other visual and aural electronic modes of communication more and more, reading books is ceasing to be the primary way of knowing something in our society.

Imagine you are male, around 16-years-old, born into a middle class family. It is Saturday around 4:30 p.m. and you are at home, bored. You have the vague sense that you have homework, but you do not feel particularly “in the mood” to do it. You want to have fun this Saturday afternoon, and do something that you want to do.

Like most adolescents today, you carry a phone and you have the choice of several hundred television stations, a small library of DVDs, and a tv set in your bedroom. Chances are that at least one additional large-screen television is located somewhere else in the house, as well as at least one computer with Internet access.

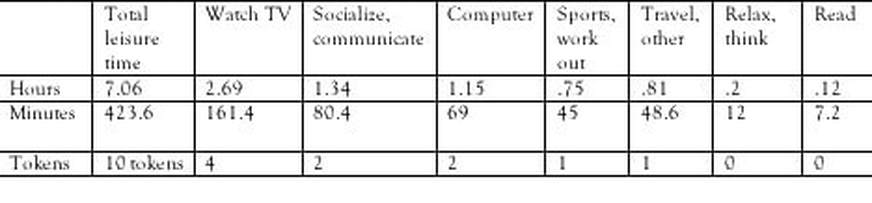

If your leisure time could be represented by 10 tokens and you had to distribute these 10 tokens across the activities you wanted to pursue over the weekend, the probable results would be as follows:

4 tokens=watching television

2 tokens=playing around on the computer

2 tokens=socializing and communicating

1 token=playing sports or working out

1 token=travel and other

0 tokens=reading

In actuality, this distribution of tokens mirrors the average time spent in leisure time activities by male and female students, aged 15-19, during 2011. Although time spent reading would not be sufficient to constitute a token, teens confessed to spending about 7 minutes per day reading, or about 1/10 of the time spent surfing on the computer and 1/23 of the time spent watching television.

Table 1: How teens, aged 15-19, spend their leisure time on weekends (daily averages)

Imagine you are male, around 16-years-old, born into a middle class family. It is Saturday around 4:30 p.m. and you are at home, bored. You have the vague sense that you have homework, but you do not feel particularly “in the mood” to do it. You want to have fun this Saturday afternoon, and do something that you want to do.

Like most adolescents today, you carry a phone and you have the choice of several hundred television stations, a small library of DVDs, and a tv set in your bedroom. Chances are that at least one additional large-screen television is located somewhere else in the house, as well as at least one computer with Internet access.

If your leisure time could be represented by 10 tokens and you had to distribute these 10 tokens across the activities you wanted to pursue over the weekend, the probable results would be as follows:

4 tokens=watching television

2 tokens=playing around on the computer

2 tokens=socializing and communicating

1 token=playing sports or working out

1 token=travel and other

0 tokens=reading

In actuality, this distribution of tokens mirrors the average time spent in leisure time activities by male and female students, aged 15-19, during 2011. Although time spent reading would not be sufficient to constitute a token, teens confessed to spending about 7 minutes per day reading, or about 1/10 of the time spent surfing on the computer and 1/23 of the time spent watching television.

Table 1: How teens, aged 15-19, spend their leisure time on weekends (daily averages)

Although teens have less leisure time on weekdays, particularly if they are enrolled in high school or college, the percentage of time spent in various activities is roughly the same as on weekends. Time spent in either reading or relaxing remains far short of the time necessary to warrant a token. The rarity of reading during the school week might seem surprising to those who assume that homework might still involve reading required texts outside of school hours. Apparently, reading is not a popular choice, even when homework is assigned. Indeed, a recent study of adolescents in a literature course found that most students read literary summaries on the Internet and took notes during discussions in class in lieu of actually reading the text. This quick and easy way of learning about a text, sometimes called “fake reading,” has become de rigeur in high schools.

Obviously, for most of their leisure time, teens are not reading books, but are using electronic devices—television, the computer, or a phone—as a way of mediating experience. Playing around with electronic media provides instant gratification and an interactive experience, while reading a book requires both work and focus. While the outcome of the interaction with electronic media is fairly certain—some pleasing sounds and images, perhaps a message from a friend, the outcome of reading a book is anything but assured. With a book, interactions take place inside the head; with electronic media, interactions are externalized and dependent on the characteristics of the machine.

The portable, ubiquitous brain

No device better represents the 21st century than today’s handy, multi-use, smart phone. Carrying along a phone is like having a portable, powerful brain in your pocket. Even if you are sitting on a beach in California, within seconds, a phone can bring up images of ancient Chinese scrolls, translate a chunk of text from Urdu to English, remind you of an appointment, check the facts behind a recent political speech, and shoot and transport a photo instantaneously to the other side of the world. Magic.

On the college campus where I work, about half of the students on their way to class walk while gazing at their phones; the other half wear earbuds. Of course, one of the most popular uses for phones these days is texting, which can and does occur any time and any place. Texting always delivers the message, even if no one is on the receiving end. Although texts are, by nature, written comments, they share characteristics associated with the spontaneous and casual utterances of oral language. However, texts also carry a sense of urgency, and, when a text is received, real pressure exists to respond as quickly as humanly possible. A heavy texter can appear to be perpetually staring at his/her phone, trying to avoid getting too far behind.

On average, adolescents send and receive more than 100 texts per day. Of course, some people text more often, such as the high school student in Sacramento who recently sent and received over 300,000 texts in a single month, an average of 10,000 texts a day, or seven messages a minute.

The centrality of the phone to contemporary life is difficult to overstate. For most adolescents, the phone has become indispensible—it is the first thing they grab in the morning and the last thing that they touch before going to sleep at night. Eighty-four percent of teens sleep with their phones within easy reach of their beds.

In addition to keeping up with texts, emails, and voicemail, teens feel compelled to monitor their status and the status of their friends on social networking websites, such as Facebook. As has been noted by self-proclaimed Cyborg Anthropologist Amber Case, students today must assiduously keep up with multiple identities—on social websites, for online gaming, with various virtual acquaintances, but also in school among peers, on a sports team, among friends, and within the family unit. A disparaging post, especially within a public group can be damaging, and a few teens have had extreme responses to derogatory remarks, including withdrawal, retaliation, and suicide.

Keeping up with multiple identities within manifold groups takes dedication and vigilance. The seemingly endless stream of news, gossip, and “urgent messages” is one of the reasons adolescents have stopped reading. Indeed, when queried about the lack of time devoted to reading books, most adolescents respond, “I just don’t have the time.”

When faster is not fast enough

Certainly, a distinguishing feature of contemporary life is its sheer speed. The time span that most humans consider an intolerable waiting period continues to shorten. A laptop computer that takes more than a ten seconds to boot up seems antiquated. A webpage that takes more than four seconds to load is unbearable.

Indeed, to wade through the information deluge at any moment in time, to keep up with trends through Twitter and Pinterest; to read the news on various websites; to peruse the most recent journals, magazines, or books (300,000 new books or editions are published every year in the United States); could take untold hours. Thus, multi-tasking has become a necessary and expected way for humans to keep up. When watching TV, for example, most viewers also operate at least one other device, such as a phone, tablet, or laptop computer.

James Gleick terms the obsession with speed, “hurry sickness,” and classifies it as a kind of psychosis.

We — those of us in the faster cities and faster societies and faster mass culture of the technocratic dawn of the third millennium C.E. — are manic. The symptoms of mania are all too familiar: volubility and fast speech; restlessness and decreased need for sleep; heightened motor activity and increased self-confidence.

Unfortunately, one of the casualties of an always-on lifestyle is that little time remains at the end of the day to sit back and think—about what is important, what is superfluous, and what is worth pursuing. Quiet moments of reflection that have traditionally accompanied reading seem fewer and far between. George Steiner notes, "there is a fierce privacy to print and claim on silence...the traits of sensibility now most suspect.” Recall from Table 1 that adolescents spend only 12 minutes per day thinking and relaxing. Apparently, most teens must “hurry up and relax” if they are going to relax at all.

Although technology can improve efficiency and speed, it is not a panacea for all problems. Yet, the belief that any field can achieve economies of scale with the proper application of technology and a concomitant reduction in costs has become widespread. Educational reformers compress four years of teacher preparation into five weeks (Teach for America), the formerly fifth grade math curriculum wends its way into the third grade (Common Core Curriculum), and the senior year of high school becomes the ideal time for taking college-credit courses.

It has become blasphemous to suggest the possibility that certain endeavors cannot be accelerated. Are there really short-cuts for becoming a world class violinist, qualifying for the Olympics in the 10,000 meter run, performing heart surgery, or teaching 30 rambunctious six-year-olds? Indeed, many endeavors, by their very nature, require years of practice, unwavering discipline, and a laser-like, intensive focus.

Yet, these time-consuming, energy-depleting habits—practice, discipline, focus—are precisely the habits that the electronic media does not encourage. Electronic media offer quick, sensory joyrides; endless distractions; and the ability to log on or shut off whenever and wherever you feel like it. Unquestionably, a tension exists between the time necessary for “slow-build” endeavors, such as building expertise and frenetic “fastpitch” endeavors, such as making the rounds in chatroulette.

In a hurry-up world, there may be little time to reflect, so decisions have to be made spontaneously, in the heat of the moment. To understand how decisions are made under pressure, research on speed-dating can help. In a speed-dating situation, participants gather in a room, then half sit at a table (usually the women), while the other half (usually the men) move from table to table every few minutes. A commercial website known as “slow dating” offers the following rationale for extending the time for actual conversation to a whopping four minutes:

We feel that three minutes is too short a time with all the moving between tables and the note taking. We strongly believe that four minutes is the right amount of time to decide whether you're prepared to invest more time in follow up emails and phone calls to land a real date with someone you meet at one of our events. Four minutes per date also enables you to meet 15-20 dates in one night without getting completely worn out.

In speed-dating situations, even under conditions that promise a full extra minute of interaction, most participants make up their minds about the other party within the first seconds of contact. That is, most participants make the decision to “like” or “dislike” instantaneously, without regard to what the other person might actually say or do during the conversation.

When stakes are high and decisions must be immediate, stress increases. A human being under stress, such as a person under attack by a grizzly bear (at a national park or at a speed-dating event), may not have time to think rationally. In most cases, stress invokes a “fight or flight” reaction.

The social milieu of words

In a hurry-up, high-stress world, words become, as William Boroughs suggested, “an ox-cart way of doing things, awkward instruments." The challenge from the grizzly bear evokes a scream, not an eloquent proclamation.

The form factor of the portable, ubiquitous brain (phone), with its tiny keys and small display makes images and abbreviations much more practical than long passages of pure, grammatically-correct text. Few individuals are going to type a precise, polysyllabic word when an emoticon or short word with approximate meaning will suffice. As the functions of phones become integrated into clothing and eyewear (a contact lens that connects with the Internet has already been developed), language will become ever more simplified.

Using emoticons and Internet acronyms slow the wear and tear on thumb muscles (from typing too much) and can still manage to communicate the gist of a message.

Example: u found digs (°⌣°). imho r e good $. hope u not nifoc. lol. Ttfn.

Translation: You found a new home? I am so happy for you. In my humble opinion, real estate is an excellent value in today’s market. I just hope that you are not naked in front of the computer right now. Oh, I am just trying to be funny (laugh out loud). Let’s talk to each other again soon (ta-ta for now).

The condensed, simplistic plainspeak of txtg (texting) aligns well with the language of other electronic media. Scripts for television shows and films are imagined transcriptions of conversations, and are written to mimic human speech, which means the inclusion of inflections (like), short words (hey), and simple sentences (Run for your life!). The more complex language found in the exposition of books gets left behind when content gets adapted for electronic media.

Websites are dominated by images and plainspeak for many reasons—to insure readability among visitors of all ages and reading levels, to make comprehension easier for international visitors (or translating machines), and to avoid alienating the multitudes, who by-and-large shun text-heavy websites. Most adolescents use the Internet to view videos or images, play games, go shopping, or visit/update their webpages. It is a rare event when an adolescent goes online to download and read one of the millions of free e-books available through Gutenberg.org, Bartleby.com, or other book-related sites.

So, in re-examining the activities from Table 1, there seems to be no time, save the few minutes spent relaxing or reading, when an adolescent might possibly encounter an unfamiliar word.

Yet, literacy researchers insist that knowledge of words is most often acquired informally, outside of school, principally through voluntary reading. Free reading has been shown to be the most accurate predictor of vocabulary growth in school-age children. Encountering an unfamiliar word while free reading does not mean that a student will automatically comprehend it, though foggy notions about the meanings of words eventually lead to more complete knowledge. It turns out that having partial knowledge of a word is advantageous--an essential step in increasing one’s vocabulary.

Although a student might have a five- to ten-percent chance of learning the meaning of any particular word from context, an encounter with 20,000 unfamiliar words translates into an increased vocabulary of up to 2,000 words. In recent years, it has been estimated that school-age children's vocabularies increase at the rate of approximately 3,000 words a year, until they reach their mid-teens.

However, if reading continues to falter as a leisure time activity, the amount of words that students will know seems likely to fall. Books are the repositories of language, and if students stop reading books, where will they encounter new words?

Words and the intellect

About the importance of language, Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure wrote, "Without language, thought is a vague, uncharted nebula. There are no pre-existing ideas and nothing is distinct before the appearance of language." Certainly, words are tools for organizing experience, interpreting sensory perceptions, and giving meaning to life events. Typically, a person’s knowledge of words corresponds with the measure of his/her general intelligence. Although one cannot determine the causal complexities in the relationships among reading comprehension, intelligence, and vocabulary knowledge with unequivocal precision, the preponderance of research suggests a strong correlation. To be sure, "the relationship between vocabulary and general intelligence is one of the most robust findings in the history of intelligence-testing."

In a study involving over 100,000 students from fifteen different countries, the median correlations between a student 's knowledge of vocabulary and reading performance ranged from .66 (18-year-olds) to .75 (14-year-olds). Other research has found that students with extensive vocabularies also seem to possess an impressive semantic understanding of the connections among words, an understanding that further aids in reading comprehension.

When students fail in school, it usually has more to do with their lack of exposure to words and their inability to comprehend on-grade-level texts than other factors, such as behavior, socio-economic status, or family background. Literacy researchers Healy and Barr write,

The use of one's own words as one is learning subject matter relieves the abstract nature of school knowledge, causing reverberations and establishing resonances between what is to be learned and what is already known. When students of any background must foreshorten this natural process, which they have used since birth to make sense of their experiences, their achievement suffers.

Robert Marzano discerns three relationships between words and thoughts:

1) Words are a form of thought,

2) Words are mediators of thought, and

3) Words are tools for enhancing thought.

According to Marzano, Words as a form of thought means that language acts as the root of human cognition, supplementing and synthesizing linguistic and nonlinguistic codes over time. Words as mediators of thought has to do with the self-talk (or covert talk) that a person uses to clarify and control his or her own thinking. Finally, because spoken and written words are the very basic tools of learning, words enhance thought. In Marzano’s formulation, a person with low vocabulary knowledge may find it difficult to understand a text, and difficulties may be exacerbated by limitations in thinking and the inability to self-reflect.

At the least, having a meager knowledge of words may be a warning of sorts, as is demonstrated by the fact that 60% of prisoners, 75% of welfare recipients, and 85% of unwed mothers can be classified as poor or dysfunctional readers. Obviously, a lack of word knowledge does not necessarily lead to a life of crime, unemployment, and sex at an early age, but poor reading and writing skills are serious impediments to academic success at all levels.

Towards an electronically-mediated, oral and visual culture

The current fashion is to insert voice recognition capabilities into more and more machines. Today, the driver of a car can change the radio station by simply telling the car to choose another station; a son can speak to his mother by telling his phone, “Call mom;” a journalist can record and transcribe an interview in real time with the help of a computer.

In his book Orality and Literacy, Walter Ong makes the claim that the structure of the brain, itself, is dependent upon how much a person reads and writes in comparison with how much a person listens and speaks. The languages of oral cultures, for example, typically contain less than five thousand words, while chirographic cultures (those based upon a written alphabet) typically contain hundreds of thousands of words. For example, there exist over a million and a half words in print in English.

The ability to capture thought into succinct, written language, according to Ong, provided the impetus for the development of modern science. That is, the sophisticated tools of language made possible the expression of complex thoughts, ideas, and intuitions, which otherwise would have gone unrecorded. Words in an oral culture are fewer and the meanings may be less precise. In an oral culture, one word may serve many functions. For example, a single word might signify all objects that fly-be it a mosquito, bird, airplane, rocket, or pilot.

In an oral culture, communication is often done in the presence of the group. At a fundamental level, oral culture relies upon sound, image, and the immediacy of the group experience, while a chirographic culture is built upon the written word and individual experience.

From this perspective, the popularity of social networking sites that are predicated on an ongoing group experience, such as Facebook, could be construed as a sign of a shift towards an oral society. The one-dimensional, unifying themes and crowdsourcing on display at recent political conventions also highlight the tendency towards groupthink and the valorization of perception over rational thought. Although most societies represent a blend of the oral and chirographic, lately, the United States seems to be moving its chirographic culture to the cloud so it can free up more space to experience the now of electronically-mediated information.

Words and biology

Although Walter Ong was a professor of English literature and philosopher, his theories have been confirmed by neuroscientists who measure physical changes and blood flow differentials in the brain through various technologies, such as Positron Emission Tomography (PET). In a recent experiment, pictures of the brains of a group of struggling readers were taken as part of a pretest. Then, the struggling readers were given 100 hours of intensive, “word therapy” to help them improve their reading comprehension. After 100 hours of word therapy, pictures of the struggling readers’ brains revealed that, as their reading comprehension improved, their brains physically changed.

Lev Vygotsky, the Russian educator who died in 1934, postulated that words were crucial to the cognitive development of children to such an extent that they could influence behavior in nonlinguistic, as well as linguistic, ways. The final sentence of Vygotsky’s book Mind and Society declares that "a word is a microcosm of human consciousness."

Since the 1980s, Yale University Psychiatrist Ralph Hoffman has adapted aspects of Vygotsky’s theories to explore the causes of schizophrenia. One of Hoffman’s major breakthroughs has been the hypothesis that verbal hallucinations or “voices" heard by schizophrenics may result from the inability to regulate their own discourse plans. Consequently, the voices that schizophrenics hear may be ideas that have somehow wandered off from their conscious brains.

Through Hoffman’s version of “word therapy," a program that teaches schizophrenics to gain control over ideas and their overt expression, verbal hallucinations have been almost totally eradicated. Thus, from two different perspectives, Vygotsky and Hoffman demonstrate the power of words to not only capture thoughts, but to direct thoughts as well.

When she encounters words, Temple Grandin, the renowned equipment designer for the livestock industry, translates “both spoken and written words into full-color movies, complete with sound, which run like a VCR tape in my head.” Grandin, who is autistic, is able to visualize complete facilities for animals without invoking words. However, when communicating her ideas to others, Grandin still must translate the images in her head into words. That she has written ten books would seem strong evidence that, even in the mind of an image-dominated savant like Temple Grandin, words play a critical role.

Goldfish in a bowl

Conjecture concerning how a transformation from words to sensations will affect how we think and live is necessarily speculative. E.M. Forster has said that "it is a mistake to think that books have come to stay. The human race did without them for thousands of years and may decide to do without them again."

However, from the time of the pre-Socratic societies of Greece to the bounty on the head of Salmon Rushdie, and every war and love affair in between, the degree to which words can empower or incapacitate has depended upon the linguistic dexterity of the user. Alfred North Whitehead has suggested that language was the primary force in the creation of the soul --"The mentality of mankind and the language of mankind created each other. The account of the sixth day should be written, 'He gave them speech, and they became souls.'"

Ernst Cassirer, in his studies of language and mythology, often writes about the sacrosanct quality of words. "There must be some particular, essentially unchanging function that endows the Word with this extraordinary, religious character, and exalts it ab initio to the religious sphere, the sphere of the 'holy.' In the creation accounts of almost all great cultural religions, the Word appears in league with the highest Lord of creation; either as the tool which he employs or actually as the primary source from which He, like all other Being and order of Being, is derived."

The medium is not only the message as Marshall MacLuhan alleged, but the propensities and constraints of media affect both the content of the message and how the message will be received. Every new medium—cars, railroads, computers, telephones, electric lights—reorganizes our consciousness, but like goldfish in a bowl, we remain unaware of the transformation.

In a culture biased towards image and sound, in a culture that has little need for words to symbolically represent social reality, the possibility exists that an individual may not possess the resources with which to express what is in the mind. If that possibility is indeed a reality, then, as the corpus of language shrinks, so shrinks human capacity for intelligent thought. One wonders what can exist in the mind to express without the language with which to express it.

In the book Crisis of Our Age, Pitirim Sorokin contends that ours is an age obsessed with the sensate--the pursuit of wealth, pleasure, and leisure, at the expense of social responsibility, virtue, and truth. For humans enraptured by the sensate, only the present moment is real and desirable; consequently the impulse is to "snatch the present kiss; get rich quick; seize the power, popularity, fame, and opportunity of the moment."

Electronic media offer an endless array of sensuous experiences and they offer them right here, right now, and without strings—no need to decode text, or even, to think rationally. Today it is possible to spend more time in the vicarious realms of electronic media than in the "real world." Many people do.

In twenty-first century society, electronic media, not religion, serves as the “opium des volkes.” It is not a religious artifact, but the big-screen television that has become the dominant artifact in contemporary homes. Adolescents do not carry around pocket-size religious texts; they carry phones.

It is well known that Plato wanted to banish the poets from his Republic. Eric Havelock in his book Preface to Plato explains why. During the time in which Plato lived, poets roamed from town to town, telling long, elaborate tales from memory in front of large crowds.

Plato did not want the poets in his Republic because he thought his fellow citizens should think for themselves. The rambling poets of Ancient Greek times were not renowned thinkers. They recited; they pandered; they performed. Havelock writes that ancient Greek poetry, "far from disclosing the true relations of things or the true definitions of the moral virtues, forms a kind of refracting screen which disguises and distorts reality and at the same time distracts us and plays tricks with us by appealing to the shallowest of our sensibilities."

Havelock’s message about the threats posed by distraction, distortion, and superficiality seems prescient. The problem is that many of us are reticent to read such a challenging text. We may lack either the vocabulary to understand it or the time to read and reflect on it. An easier course of action would be to wait for the film adaptation and maybe order it through Netflix.

Obviously, for most of their leisure time, teens are not reading books, but are using electronic devices—television, the computer, or a phone—as a way of mediating experience. Playing around with electronic media provides instant gratification and an interactive experience, while reading a book requires both work and focus. While the outcome of the interaction with electronic media is fairly certain—some pleasing sounds and images, perhaps a message from a friend, the outcome of reading a book is anything but assured. With a book, interactions take place inside the head; with electronic media, interactions are externalized and dependent on the characteristics of the machine.

The portable, ubiquitous brain

No device better represents the 21st century than today’s handy, multi-use, smart phone. Carrying along a phone is like having a portable, powerful brain in your pocket. Even if you are sitting on a beach in California, within seconds, a phone can bring up images of ancient Chinese scrolls, translate a chunk of text from Urdu to English, remind you of an appointment, check the facts behind a recent political speech, and shoot and transport a photo instantaneously to the other side of the world. Magic.

On the college campus where I work, about half of the students on their way to class walk while gazing at their phones; the other half wear earbuds. Of course, one of the most popular uses for phones these days is texting, which can and does occur any time and any place. Texting always delivers the message, even if no one is on the receiving end. Although texts are, by nature, written comments, they share characteristics associated with the spontaneous and casual utterances of oral language. However, texts also carry a sense of urgency, and, when a text is received, real pressure exists to respond as quickly as humanly possible. A heavy texter can appear to be perpetually staring at his/her phone, trying to avoid getting too far behind.

On average, adolescents send and receive more than 100 texts per day. Of course, some people text more often, such as the high school student in Sacramento who recently sent and received over 300,000 texts in a single month, an average of 10,000 texts a day, or seven messages a minute.

The centrality of the phone to contemporary life is difficult to overstate. For most adolescents, the phone has become indispensible—it is the first thing they grab in the morning and the last thing that they touch before going to sleep at night. Eighty-four percent of teens sleep with their phones within easy reach of their beds.

In addition to keeping up with texts, emails, and voicemail, teens feel compelled to monitor their status and the status of their friends on social networking websites, such as Facebook. As has been noted by self-proclaimed Cyborg Anthropologist Amber Case, students today must assiduously keep up with multiple identities—on social websites, for online gaming, with various virtual acquaintances, but also in school among peers, on a sports team, among friends, and within the family unit. A disparaging post, especially within a public group can be damaging, and a few teens have had extreme responses to derogatory remarks, including withdrawal, retaliation, and suicide.

Keeping up with multiple identities within manifold groups takes dedication and vigilance. The seemingly endless stream of news, gossip, and “urgent messages” is one of the reasons adolescents have stopped reading. Indeed, when queried about the lack of time devoted to reading books, most adolescents respond, “I just don’t have the time.”

When faster is not fast enough

Certainly, a distinguishing feature of contemporary life is its sheer speed. The time span that most humans consider an intolerable waiting period continues to shorten. A laptop computer that takes more than a ten seconds to boot up seems antiquated. A webpage that takes more than four seconds to load is unbearable.

Indeed, to wade through the information deluge at any moment in time, to keep up with trends through Twitter and Pinterest; to read the news on various websites; to peruse the most recent journals, magazines, or books (300,000 new books or editions are published every year in the United States); could take untold hours. Thus, multi-tasking has become a necessary and expected way for humans to keep up. When watching TV, for example, most viewers also operate at least one other device, such as a phone, tablet, or laptop computer.

James Gleick terms the obsession with speed, “hurry sickness,” and classifies it as a kind of psychosis.

We — those of us in the faster cities and faster societies and faster mass culture of the technocratic dawn of the third millennium C.E. — are manic. The symptoms of mania are all too familiar: volubility and fast speech; restlessness and decreased need for sleep; heightened motor activity and increased self-confidence.

Unfortunately, one of the casualties of an always-on lifestyle is that little time remains at the end of the day to sit back and think—about what is important, what is superfluous, and what is worth pursuing. Quiet moments of reflection that have traditionally accompanied reading seem fewer and far between. George Steiner notes, "there is a fierce privacy to print and claim on silence...the traits of sensibility now most suspect.” Recall from Table 1 that adolescents spend only 12 minutes per day thinking and relaxing. Apparently, most teens must “hurry up and relax” if they are going to relax at all.

Although technology can improve efficiency and speed, it is not a panacea for all problems. Yet, the belief that any field can achieve economies of scale with the proper application of technology and a concomitant reduction in costs has become widespread. Educational reformers compress four years of teacher preparation into five weeks (Teach for America), the formerly fifth grade math curriculum wends its way into the third grade (Common Core Curriculum), and the senior year of high school becomes the ideal time for taking college-credit courses.

It has become blasphemous to suggest the possibility that certain endeavors cannot be accelerated. Are there really short-cuts for becoming a world class violinist, qualifying for the Olympics in the 10,000 meter run, performing heart surgery, or teaching 30 rambunctious six-year-olds? Indeed, many endeavors, by their very nature, require years of practice, unwavering discipline, and a laser-like, intensive focus.

Yet, these time-consuming, energy-depleting habits—practice, discipline, focus—are precisely the habits that the electronic media does not encourage. Electronic media offer quick, sensory joyrides; endless distractions; and the ability to log on or shut off whenever and wherever you feel like it. Unquestionably, a tension exists between the time necessary for “slow-build” endeavors, such as building expertise and frenetic “fastpitch” endeavors, such as making the rounds in chatroulette.

In a hurry-up world, there may be little time to reflect, so decisions have to be made spontaneously, in the heat of the moment. To understand how decisions are made under pressure, research on speed-dating can help. In a speed-dating situation, participants gather in a room, then half sit at a table (usually the women), while the other half (usually the men) move from table to table every few minutes. A commercial website known as “slow dating” offers the following rationale for extending the time for actual conversation to a whopping four minutes:

We feel that three minutes is too short a time with all the moving between tables and the note taking. We strongly believe that four minutes is the right amount of time to decide whether you're prepared to invest more time in follow up emails and phone calls to land a real date with someone you meet at one of our events. Four minutes per date also enables you to meet 15-20 dates in one night without getting completely worn out.

In speed-dating situations, even under conditions that promise a full extra minute of interaction, most participants make up their minds about the other party within the first seconds of contact. That is, most participants make the decision to “like” or “dislike” instantaneously, without regard to what the other person might actually say or do during the conversation.

When stakes are high and decisions must be immediate, stress increases. A human being under stress, such as a person under attack by a grizzly bear (at a national park or at a speed-dating event), may not have time to think rationally. In most cases, stress invokes a “fight or flight” reaction.

The social milieu of words

In a hurry-up, high-stress world, words become, as William Boroughs suggested, “an ox-cart way of doing things, awkward instruments." The challenge from the grizzly bear evokes a scream, not an eloquent proclamation.

The form factor of the portable, ubiquitous brain (phone), with its tiny keys and small display makes images and abbreviations much more practical than long passages of pure, grammatically-correct text. Few individuals are going to type a precise, polysyllabic word when an emoticon or short word with approximate meaning will suffice. As the functions of phones become integrated into clothing and eyewear (a contact lens that connects with the Internet has already been developed), language will become ever more simplified.

Using emoticons and Internet acronyms slow the wear and tear on thumb muscles (from typing too much) and can still manage to communicate the gist of a message.

Example: u found digs (°⌣°). imho r e good $. hope u not nifoc. lol. Ttfn.

Translation: You found a new home? I am so happy for you. In my humble opinion, real estate is an excellent value in today’s market. I just hope that you are not naked in front of the computer right now. Oh, I am just trying to be funny (laugh out loud). Let’s talk to each other again soon (ta-ta for now).

The condensed, simplistic plainspeak of txtg (texting) aligns well with the language of other electronic media. Scripts for television shows and films are imagined transcriptions of conversations, and are written to mimic human speech, which means the inclusion of inflections (like), short words (hey), and simple sentences (Run for your life!). The more complex language found in the exposition of books gets left behind when content gets adapted for electronic media.

Websites are dominated by images and plainspeak for many reasons—to insure readability among visitors of all ages and reading levels, to make comprehension easier for international visitors (or translating machines), and to avoid alienating the multitudes, who by-and-large shun text-heavy websites. Most adolescents use the Internet to view videos or images, play games, go shopping, or visit/update their webpages. It is a rare event when an adolescent goes online to download and read one of the millions of free e-books available through Gutenberg.org, Bartleby.com, or other book-related sites.

So, in re-examining the activities from Table 1, there seems to be no time, save the few minutes spent relaxing or reading, when an adolescent might possibly encounter an unfamiliar word.

Yet, literacy researchers insist that knowledge of words is most often acquired informally, outside of school, principally through voluntary reading. Free reading has been shown to be the most accurate predictor of vocabulary growth in school-age children. Encountering an unfamiliar word while free reading does not mean that a student will automatically comprehend it, though foggy notions about the meanings of words eventually lead to more complete knowledge. It turns out that having partial knowledge of a word is advantageous--an essential step in increasing one’s vocabulary.

Although a student might have a five- to ten-percent chance of learning the meaning of any particular word from context, an encounter with 20,000 unfamiliar words translates into an increased vocabulary of up to 2,000 words. In recent years, it has been estimated that school-age children's vocabularies increase at the rate of approximately 3,000 words a year, until they reach their mid-teens.

However, if reading continues to falter as a leisure time activity, the amount of words that students will know seems likely to fall. Books are the repositories of language, and if students stop reading books, where will they encounter new words?

Words and the intellect

About the importance of language, Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure wrote, "Without language, thought is a vague, uncharted nebula. There are no pre-existing ideas and nothing is distinct before the appearance of language." Certainly, words are tools for organizing experience, interpreting sensory perceptions, and giving meaning to life events. Typically, a person’s knowledge of words corresponds with the measure of his/her general intelligence. Although one cannot determine the causal complexities in the relationships among reading comprehension, intelligence, and vocabulary knowledge with unequivocal precision, the preponderance of research suggests a strong correlation. To be sure, "the relationship between vocabulary and general intelligence is one of the most robust findings in the history of intelligence-testing."

In a study involving over 100,000 students from fifteen different countries, the median correlations between a student 's knowledge of vocabulary and reading performance ranged from .66 (18-year-olds) to .75 (14-year-olds). Other research has found that students with extensive vocabularies also seem to possess an impressive semantic understanding of the connections among words, an understanding that further aids in reading comprehension.

When students fail in school, it usually has more to do with their lack of exposure to words and their inability to comprehend on-grade-level texts than other factors, such as behavior, socio-economic status, or family background. Literacy researchers Healy and Barr write,

The use of one's own words as one is learning subject matter relieves the abstract nature of school knowledge, causing reverberations and establishing resonances between what is to be learned and what is already known. When students of any background must foreshorten this natural process, which they have used since birth to make sense of their experiences, their achievement suffers.

Robert Marzano discerns three relationships between words and thoughts:

1) Words are a form of thought,

2) Words are mediators of thought, and

3) Words are tools for enhancing thought.

According to Marzano, Words as a form of thought means that language acts as the root of human cognition, supplementing and synthesizing linguistic and nonlinguistic codes over time. Words as mediators of thought has to do with the self-talk (or covert talk) that a person uses to clarify and control his or her own thinking. Finally, because spoken and written words are the very basic tools of learning, words enhance thought. In Marzano’s formulation, a person with low vocabulary knowledge may find it difficult to understand a text, and difficulties may be exacerbated by limitations in thinking and the inability to self-reflect.

At the least, having a meager knowledge of words may be a warning of sorts, as is demonstrated by the fact that 60% of prisoners, 75% of welfare recipients, and 85% of unwed mothers can be classified as poor or dysfunctional readers. Obviously, a lack of word knowledge does not necessarily lead to a life of crime, unemployment, and sex at an early age, but poor reading and writing skills are serious impediments to academic success at all levels.

Towards an electronically-mediated, oral and visual culture

The current fashion is to insert voice recognition capabilities into more and more machines. Today, the driver of a car can change the radio station by simply telling the car to choose another station; a son can speak to his mother by telling his phone, “Call mom;” a journalist can record and transcribe an interview in real time with the help of a computer.

In his book Orality and Literacy, Walter Ong makes the claim that the structure of the brain, itself, is dependent upon how much a person reads and writes in comparison with how much a person listens and speaks. The languages of oral cultures, for example, typically contain less than five thousand words, while chirographic cultures (those based upon a written alphabet) typically contain hundreds of thousands of words. For example, there exist over a million and a half words in print in English.

The ability to capture thought into succinct, written language, according to Ong, provided the impetus for the development of modern science. That is, the sophisticated tools of language made possible the expression of complex thoughts, ideas, and intuitions, which otherwise would have gone unrecorded. Words in an oral culture are fewer and the meanings may be less precise. In an oral culture, one word may serve many functions. For example, a single word might signify all objects that fly-be it a mosquito, bird, airplane, rocket, or pilot.

In an oral culture, communication is often done in the presence of the group. At a fundamental level, oral culture relies upon sound, image, and the immediacy of the group experience, while a chirographic culture is built upon the written word and individual experience.

From this perspective, the popularity of social networking sites that are predicated on an ongoing group experience, such as Facebook, could be construed as a sign of a shift towards an oral society. The one-dimensional, unifying themes and crowdsourcing on display at recent political conventions also highlight the tendency towards groupthink and the valorization of perception over rational thought. Although most societies represent a blend of the oral and chirographic, lately, the United States seems to be moving its chirographic culture to the cloud so it can free up more space to experience the now of electronically-mediated information.

Words and biology

Although Walter Ong was a professor of English literature and philosopher, his theories have been confirmed by neuroscientists who measure physical changes and blood flow differentials in the brain through various technologies, such as Positron Emission Tomography (PET). In a recent experiment, pictures of the brains of a group of struggling readers were taken as part of a pretest. Then, the struggling readers were given 100 hours of intensive, “word therapy” to help them improve their reading comprehension. After 100 hours of word therapy, pictures of the struggling readers’ brains revealed that, as their reading comprehension improved, their brains physically changed.

Lev Vygotsky, the Russian educator who died in 1934, postulated that words were crucial to the cognitive development of children to such an extent that they could influence behavior in nonlinguistic, as well as linguistic, ways. The final sentence of Vygotsky’s book Mind and Society declares that "a word is a microcosm of human consciousness."

Since the 1980s, Yale University Psychiatrist Ralph Hoffman has adapted aspects of Vygotsky’s theories to explore the causes of schizophrenia. One of Hoffman’s major breakthroughs has been the hypothesis that verbal hallucinations or “voices" heard by schizophrenics may result from the inability to regulate their own discourse plans. Consequently, the voices that schizophrenics hear may be ideas that have somehow wandered off from their conscious brains.

Through Hoffman’s version of “word therapy," a program that teaches schizophrenics to gain control over ideas and their overt expression, verbal hallucinations have been almost totally eradicated. Thus, from two different perspectives, Vygotsky and Hoffman demonstrate the power of words to not only capture thoughts, but to direct thoughts as well.

When she encounters words, Temple Grandin, the renowned equipment designer for the livestock industry, translates “both spoken and written words into full-color movies, complete with sound, which run like a VCR tape in my head.” Grandin, who is autistic, is able to visualize complete facilities for animals without invoking words. However, when communicating her ideas to others, Grandin still must translate the images in her head into words. That she has written ten books would seem strong evidence that, even in the mind of an image-dominated savant like Temple Grandin, words play a critical role.

Goldfish in a bowl

Conjecture concerning how a transformation from words to sensations will affect how we think and live is necessarily speculative. E.M. Forster has said that "it is a mistake to think that books have come to stay. The human race did without them for thousands of years and may decide to do without them again."

However, from the time of the pre-Socratic societies of Greece to the bounty on the head of Salmon Rushdie, and every war and love affair in between, the degree to which words can empower or incapacitate has depended upon the linguistic dexterity of the user. Alfred North Whitehead has suggested that language was the primary force in the creation of the soul --"The mentality of mankind and the language of mankind created each other. The account of the sixth day should be written, 'He gave them speech, and they became souls.'"

Ernst Cassirer, in his studies of language and mythology, often writes about the sacrosanct quality of words. "There must be some particular, essentially unchanging function that endows the Word with this extraordinary, religious character, and exalts it ab initio to the religious sphere, the sphere of the 'holy.' In the creation accounts of almost all great cultural religions, the Word appears in league with the highest Lord of creation; either as the tool which he employs or actually as the primary source from which He, like all other Being and order of Being, is derived."

The medium is not only the message as Marshall MacLuhan alleged, but the propensities and constraints of media affect both the content of the message and how the message will be received. Every new medium—cars, railroads, computers, telephones, electric lights—reorganizes our consciousness, but like goldfish in a bowl, we remain unaware of the transformation.

In a culture biased towards image and sound, in a culture that has little need for words to symbolically represent social reality, the possibility exists that an individual may not possess the resources with which to express what is in the mind. If that possibility is indeed a reality, then, as the corpus of language shrinks, so shrinks human capacity for intelligent thought. One wonders what can exist in the mind to express without the language with which to express it.

In the book Crisis of Our Age, Pitirim Sorokin contends that ours is an age obsessed with the sensate--the pursuit of wealth, pleasure, and leisure, at the expense of social responsibility, virtue, and truth. For humans enraptured by the sensate, only the present moment is real and desirable; consequently the impulse is to "snatch the present kiss; get rich quick; seize the power, popularity, fame, and opportunity of the moment."

Electronic media offer an endless array of sensuous experiences and they offer them right here, right now, and without strings—no need to decode text, or even, to think rationally. Today it is possible to spend more time in the vicarious realms of electronic media than in the "real world." Many people do.

In twenty-first century society, electronic media, not religion, serves as the “opium des volkes.” It is not a religious artifact, but the big-screen television that has become the dominant artifact in contemporary homes. Adolescents do not carry around pocket-size religious texts; they carry phones.

It is well known that Plato wanted to banish the poets from his Republic. Eric Havelock in his book Preface to Plato explains why. During the time in which Plato lived, poets roamed from town to town, telling long, elaborate tales from memory in front of large crowds.

Plato did not want the poets in his Republic because he thought his fellow citizens should think for themselves. The rambling poets of Ancient Greek times were not renowned thinkers. They recited; they pandered; they performed. Havelock writes that ancient Greek poetry, "far from disclosing the true relations of things or the true definitions of the moral virtues, forms a kind of refracting screen which disguises and distorts reality and at the same time distracts us and plays tricks with us by appealing to the shallowest of our sensibilities."

Havelock’s message about the threats posed by distraction, distortion, and superficiality seems prescient. The problem is that many of us are reticent to read such a challenging text. We may lack either the vocabulary to understand it or the time to read and reflect on it. An easier course of action would be to wait for the film adaptation and maybe order it through Netflix.